March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. View of downtown Mostar and the Neretva river. Mostar, the largest city in Herzegovina, saw fierce fighting during the war between its Croat and its Muslim Bosniak communities. Like Sarajevo, it was before the war a symbol of a cosmopolitan Bosnian society where all communities cohabited peacefully. Nowadays, it is a divided city along the border formed by the Neretva river, the Croats on one side, the Muslims on the other. Each community has its own police stations, fire stations, bus station, football team and of course its own schools and university where different versions of the same history are being taught.

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The waters of the Neretva river. Mostar, the largest city in Herzegovina, saw fierce fighting during the war between its Croat and its Muslim Bosniak communities. Like Sarajevo, it was before the war a symbol of a cosmopolitan Bosnian society where all communities cohabited peacefully. Nowadays, it is a divided city along the border formed by the Neretva river, the Croats on one side, the Muslims on the other. Each community has its own police stations, fire stations, bus station, football team and of course its own schools and university where different versions of the same history are being taught.

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Lorens Listo, Mostar bridge diver and 11-year champion of the bridge diving competition, poses near the Mostar bridge.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Muslim woman on the Old Bridge of Mostar.

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Students hanging out on the site of The Partisan Memorial Cemetery in Mostar. The memorial was built in 1965 in honor of the Yugoslav Partisans of Mostar who were killed during World War II in Yugoslavia.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. A playground in downtown Mostar.

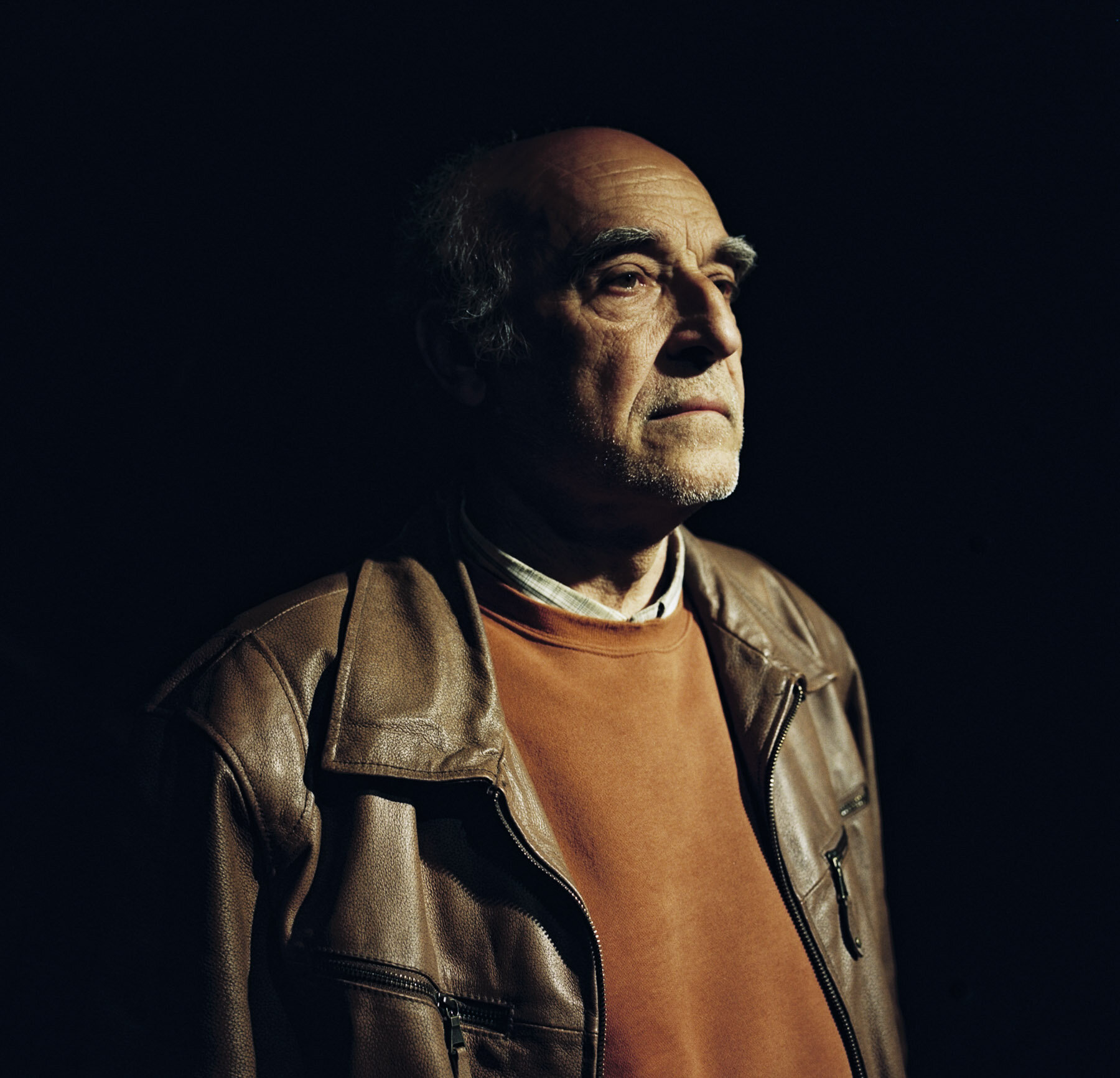

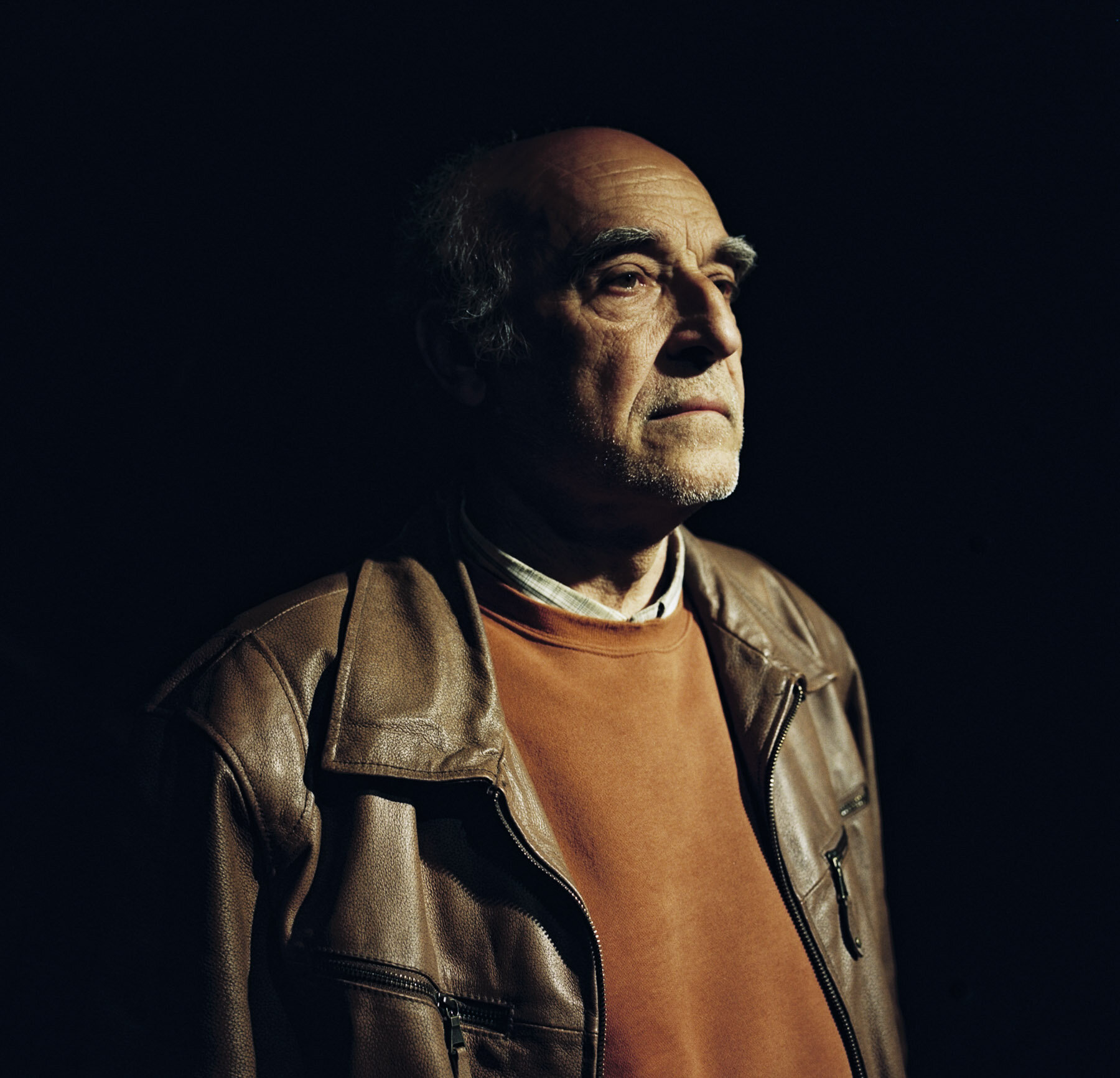

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Mladen Lubic, Croat war veteran from the Viper Brigade of Široki Brijeg, and one of the vocal leaders of the Croat community in Mostar.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Croat community on a catholic procession on the hills around Mostar. This 14-station religious procession by the fervent local Croat community commemorates the suffering of the Christ.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Catholic priest from Medjugorje photographed after the mass and the procession on the hills around Mostar by the local Croat community. This 14-station religious procession by the fervent local Croat community commemorates the suffering of the Christ.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Croat community on a catholic procession on the hills around Mostar. This 14-station religious procession by the fervent local Croat community commemorates the suffering of the Christ.

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Millennium Cross - or Mostar Cross - stands tall on Hum hill which is the highest peak in the Mostar region and directly dominates the divided city. In 2001, the UNESCO and the city of Mostar announced the reconstruction plans for the Old Bridge. Various Croat political leaders then responded by building the catholic Millenium Cross to dominate the city as many Croats perceive the Old Bridge as a Muslim symbol. The cross is 33 meters high and was erected in 2002 to represent two thousand years of Christianity. The cross is supposed to mark a new start. Many among Mostar’s Muslim community perceive the cross as offensive and humiliating.

January 16th 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. View of the old city of sarajevo on a foggy winter day taken from the Yellow Bastion. In the foreground the Kovaci cemetery where Alija Izetbegovic, first President Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is burried.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sead Dulic, former officer in the Bosnian army, is an author and theater director who founded the Mostar Youth Theatre 1974 in 2011. He is also an activist who works towards reconciliation;

January 16th 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Street and grocery store in the old part of town.

April 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ohran Maslo, born in 1978, is a Bosniak war veteran, rock musician and the founder of the Mostar Rock School. Since 2012 and thanks to funding by the USAID and the Norwegian and swedish embassies, the school offers music lessons and acts as a band agent and Booking agent inside the local music scene. the school is one of the very few places in town where youth from both Croat and Muslim communities can freely mix.

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Jurica Simunovic, a 21-year-old medical technician and guitar teacher at the Mostar Rock School during a lesson.

March 2019. Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ana mikolic, a 19-year-old student from Siroki Brijeg, during a singing lesson at the Mostar Rock School.

January 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city on a foggy winter night.

January 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city on a foggy winter night.

January 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city on a foggy winter night.

January 19th 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Kerima Kosovac (20) and Nervia (20), are two Sarajevan student from the University of Sarajevo. Kerima studies islamology and Nervia studies Turkish, Persian and Arabic languages. In the background, the Istiklal mosque, one of the largest in the city, which was a gift from the Indonesian government to the Bosnian people.

January 21st 2020. Njuhe, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Adnan Karovic (33), Muslim Bosnian chicken-farm owner and self-taught drone builder.

January 2020. Visegrád, Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge over the Drina river. It is a historic bridge completed in 1577 by the Ottoman court architect Mimar Sinan. The UNESCO included the bridge in its 2007 World Heritage List. During the Bosnian war it was the site of massacres of Bosniaks by the Bosnian serb militias.

January 2020. Visegrád, Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Simo, 83, is a Serbian refugee from Sarajevo (vogosca)n who had to relocate to Visegrad. « I feel like a refugee in my own country. I feel very sad, no one benefited from the war. »The Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge over the Drina river. It is a historic bridge completed in 1577 by the Ottoman court architect Mimar Sinan. The UNESCO included the bridge in its 2007 World Heritage List. During the Bosnian war it was the site of massacres of Bosniaks by the Bosnian serb militias.

January 2020. Bosnia and Herzegovina. Monument to the Battle of Wounded, known as the Makljen Spomenik. This spomenik complex at Makljen Pass commemorates the Partisan soldiers who fought and gave their lives during the Battle of the Neretva where Partisans under the command of Josip Tito defended the Neretva River valley preventing Axis troops from attacking 4000 wounded Partisans at the nearby Central Hospital during late February/early March of 1943. The elusive and deceiving strategy designed by Tito for this battle/escape is considered a fit of tactical genius. But as many spomeniks built in former Yugoslavia, it is first and foremost a construction meant to memorialise the fight against Fascism. In 2000, vandals used dynamite to destroy the sculpture's facade. Only the structural reinforced concrete skeleton of the monument now still stands tall as the vestige of a bygone Yugoslavian dream.Janvier 2020. Bosnie-Herzégovine. Le spomenik de Makljen est un mémorial à la gloire des partisans yougoslaves de Tito qui donnèrent leur vie lors de la bataille de la Neretva en février/mars 1943 pour défendre la vallée de la Neretva et protéger les 4000 soldats partisans blessés de l’hopital central attaqué par les forces de l’Axe. Détruit en partie par des nationalistes croates en 2000, sa structure tient encore debout pour nous rappeler la lutte anti-fasciste des partisans pendant la seconde guerre mondiale.

January 2020. Visegrád, Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Aleksandar Topalovic is the Orthodox priest of the Church of the Virgin Mary in Visegrad. 48 from Rudo. He claims Rudo is a place where the faith is strong and many priests come from there. He claims that because the people could not be fully Serbian or Muslim or Croat during Yugoslavia, the war happened. He doesn’t think that religion is a reason for war but he agrees that nationalist politicians use the religious argument to defend their agenda. » He says in Visegrad that they have an inter-religious committee with the imam and catho priest and cohabitation works well.

January 2020. Visegrád, Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Aleksandar Topalovic is the Orthodox priest of the Church of the Virgin Mary in Visegrad. 48 from Rudo. He claims Rudo is a place where the faith is strong and many priests come from there. He claims that because the people could not be fully Serbian or Muslim or Croat during Yugoslavia, the war happened. He doesn’t think that religion is a reason for war but he agrees that nationalist politicians use the religious argument to defend their agenda. » He says in Visegrad that they have an inter-religious committee with the imam and catho priest and cohabitation works well.

January 2020. Visegrád, Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. View of Andricgrad and the Church of Saint Prince Lazar at night.

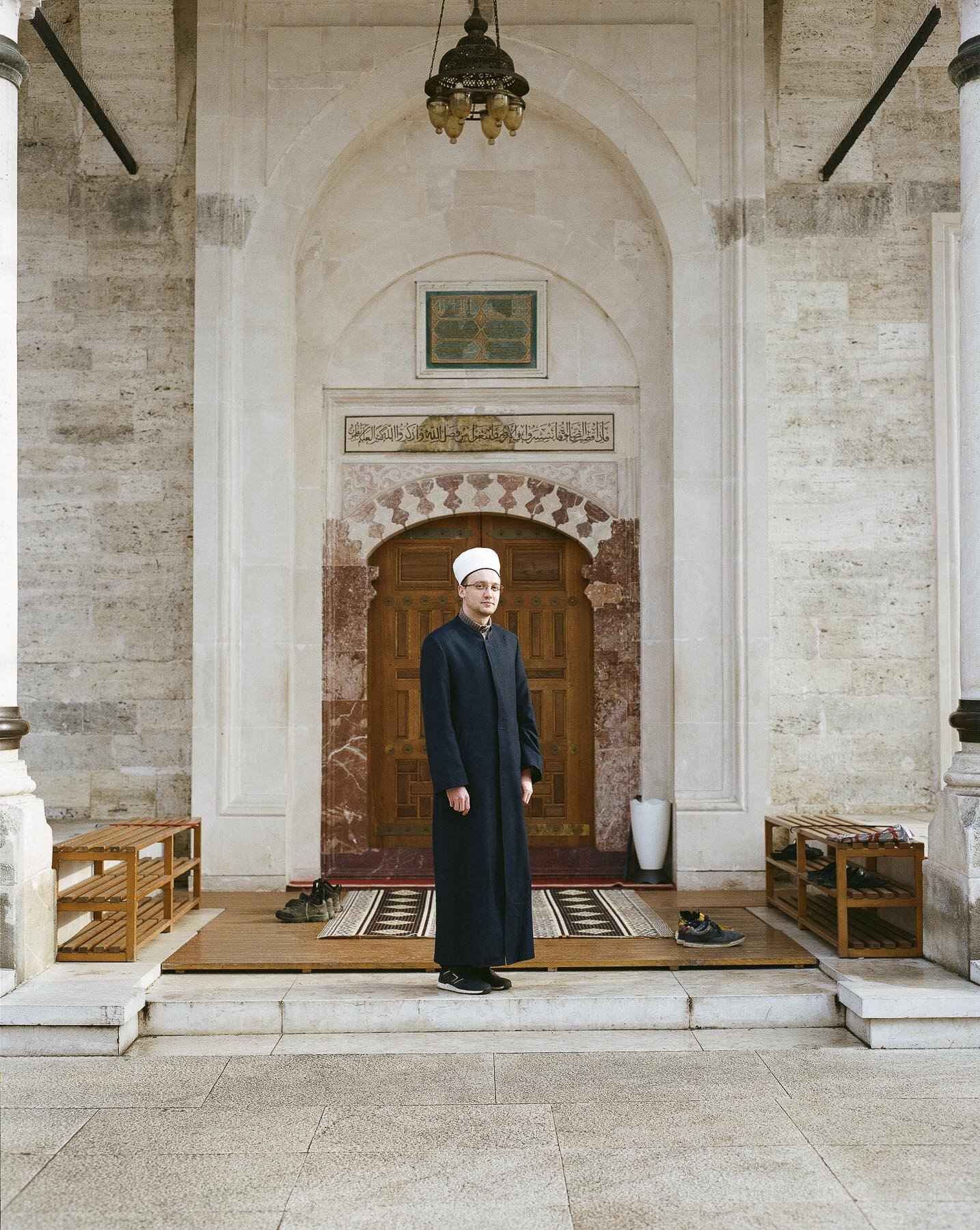

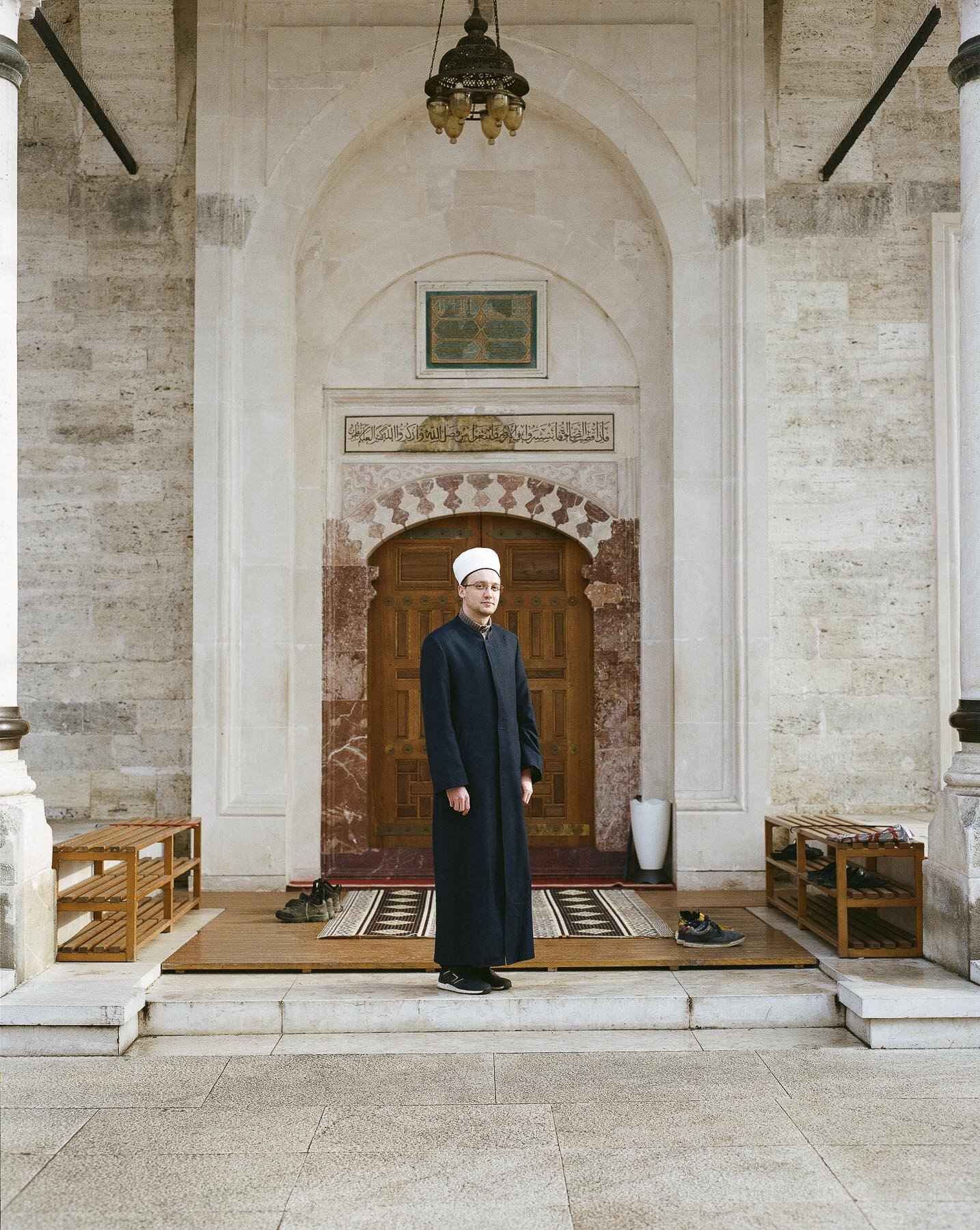

January 2020. Banja Luka, Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Muamer Okanovic, born in 1992, Imam of the Ferhadi mosque in Banja Luka. He did his madtrassa in Tuzla and graduated in Oman. « The situation is better now than it was Ten or fifteen years ago. » Banja Luka is the second largest city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the de facto capital of its Republika Srpska entity.

January 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city on a foggy winter night.

January 2020. Potočari, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial, officially known as the Srebrenica–Potočari Memorial and Cemetery for the Victims of the 1995 Genocide, is the memorial-cemetery complex in Srebrenica set up to honour the victims of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide

January 2020. Potocari, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Asim Dedic, born 1976, is a survivor of the Srebrenica genocide.« We live together but in order to make things better we need to change politicians and memory of genocide should be acknowledged. Before the war all communities were living well together. Foreign influences are a reason for the war as Yugoslavia was too powerful. Prob America. Local Serbs with the support of Serb Republic started the war. Politicians wanted the territory and things led to another. How do your Neighbours turn against you when life is fine between you: they were fed lies by politicians ».

January 2020. Urkovići, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Urkovići is a village in the municipality of Bratunac, a town and municipality located in easternmost part of Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

January 2020. Glogova, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Glogova is a village in the municipality of Bratunac.

January 23rd 2020. Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Muhizim Omerović Džile, a Bosnian army veteran and Srebrenica genocide survivor, in his home. After defending the enclave of Srebrenica from 1992 to 1995 against the Bosnian-Serb troops of Ratko Mladić, he was one of the few Bosniak men who managed to escape the massacres that followed the fall of the enclave. It is estimated that 8000 Bosniak men, some as young as 14 years of age, were executed in a methodical manner by Serb militias and buried in mass graves over the course of 10 days in July 1995. The Srebrenica genocide remains a stain on the history of the UN and European nations, which had pledged to protect the civilian populations who sought refuge in the Srebrenica « safe area ». In 2004, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia ruled that the massacre of the enclave's male inhabitants constituted genocide, a crime under international law. It is considered to be the worse atrocity to have happened on European Soil since the end WWII. After escaping, Muhizim Džile had to hide for two months in the Bosnian woods but is one of the few who managed to reach the Bosnian-held land near Tuzla. After many years as a refuge abroad (Switzerland for 4 years and then islamic studies in Iran), he decided to come back to Srebrenica to settle down with his family. In 2005, he was one of the initiators of the march for peace, which every year in july gathers thousands of people on a 3-day march to commemorate the march of death taken by many Bosnian men in Srebrenica. He says that he is now resigned by the situation in the country and he wishes his children can leave the country soon for a better future somewhere else.23 Janvier 2020. Srebrenica, Bosnie-Herzégovine. Muhizim Omerović Džile, un vétéran de l’amée bosniaque et survivant du massacre de Srebrenica. Après avoir défendu l’enclave de Srebrenica jusqu’au dernier moment, il décida de s’enfuire juste avant l’arriv

January 2020. Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Son of Muhizim Omerović Džile.

January 2020. Prijedor, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

January 2020. Sanski Most, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Šušnjar Memorial spomenik Complex was completed in 1970 and was built not only as a memorial to the thousands of victims of the Axis occupation and oppression in the surrounding region, but also, this is a memorial to the victims of the "Rebellion of the Sana Peasants", in which the local population of Sanski Most area revolted against the oppression by the Ustaše occupying forces in the first weeks of the war.

January 2020. Gornji Dabar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Serb orthodox cemetery in Gornji Dabar, a hamlet in the Western part of BiH.

January 2020. Bosnia and Herzegovina. Valley near the municipality of Prozor-Rama.

January 2020. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city on a foggy winter night.

Minor Differences

Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH), twenty-five years after the war

“You Europeans should be careful”, a politician from the Bosnian social-liberal party Naša Stranka told me, last year in Mostar. “When you look at Bosnia, you see your past. But it might very well also be your future”.

The year 2020 marks the 25th anniversary of the end of the war in BiH, mostly as a consequence of the unspeakable Srebrenica and Markale market massacres which triggered in 1995 the long-overdue NATO intervention. Within the Yugoslav federation, BiH was the most ethnically diverse state, epitomizing the utopia of a cosmopolitan society within the Balkans, a region ravaged by ethnic-religious wars for two centuries. More than a communist system, it is a dream of diversity and inclusiveness which disintegrated with Yugoslavia’s collapse.

The “Minor Differences” project, a collaboration between French photographer Patrick Wack and French writer Julien Syrac. looks at one enduring conflict in a small European country, while assessing its inability, over time, to find harmony. Through this project, we wish to portray Bosnia as a mirror, distant yet familiar, archaic yet modern, but more than ever necessary to our understanding of the European and Western realities.

Author and psychiatrist Gilbert Diatkine applied the Freudian theory of “narcissism of minor differences” to the war in Bosnia: “When friction between the states of Yugoslavia started appearing, we hoped they would find a political solution, until the war seemed unavoidable. One could have then hoped that everything that united these very similar communities sets a limit to the destructions to the very necessary, and that the rules of war and human rights be strictly respected. However, it is exactly the contrary that happened: as always when war involves “sister nations”, it is sadism that takes over with unlimited barbarism”.

The war itself and its direct aftermath were widely documented. We see our project as intervening in a third stage of the evolution of the country, as nationalism and divisive discourses are on the rise again. We intend to ask how this war and its horrors were possible, which historical and cultural reasons fostered them and why, twenty-five years later, the same tensions reappear. We believe an incomplete reconciliation does not allow for the much-needed avenues towards a harmonious and sustainable democratic society.

The project, initiated in 2019 and still in progress, envisions itself at the crossroads of the journalistic report, the literary meditation and the travel log. A selection of images is included followed by Syrac’s introductory text. We envision a final publication on time for the 25th anniversary of the end of the war in December 2020.

A quarter of a century later, this project takes us into contemporary Bosnia’s cloudy eyes and broken hearts, shining a light on the dangers of divisive populism as we are rethinking Europe. With Yugoslavia died a dream of peaceful coexistence. Could their past become our future?